Today, I want to talk about a book that has helped to expand my view of music history over the last year.

But first, how about some advice?

I’m starting a monthly music advice column. Do you need help with your music or music career? Let me take a stab at it! Send your thoughts, feelings, questions, and concerns to zw.helps.you@gmail.com and keep an eye out for the first edition next month.

Now back to our regularly scheduled programming.

I love reading about music…

It dawned on me the other day that, as subscribers to a newsletter all about music, y’all might share my interest in reading music books. When I was beginning my career, it became pretty apparent to me that I needed to always be learning if I wanted to stay relevant. Once I began teaching as well, that strong recommendation became non-negotiable at that point. Thankfully, I was never too hung up about that.

I have always loved learning. I remember feeling a palpable sense of excitement in school whenever I would wrap my head around a new idea or concept. That same feeling (though magnified 10x) extended to music as well. Even now, when I finally wrap my head around a new idea or concept, I can’t help but feel giddy.

…but rarely music history

One area that I’ve struggled with more and more as I’ve gotten older is music history. It isn’t that I dislike music history. In fact, I love music history. I’ve often told people in passing that if I wasn’t so obsessed with music, I would’ve studied history. Instead, what I take issue with is how music history is taught and the outsized effect it has on our musical present.

History is not a neutral record of past events, as much as we’d like it to be. Look at it this way: say a carnival rolls through town for one night only and you are a reporter tasked with covering it, though you are unable to attend it yourself. So, you go and collect statements about the carnival from different people in town who attended in an effort to piece together a record of the evening’s festivities. As anybody can imagine, you get a different story from everybody. There was a lot going on at the carnival and people prioritized seeing and experiencing the things that mattered to them the most. You get a lot of information, but you only have so many words that you can publish. How do you prioritize what gets said and what gets left out?

I offer up such a small example in an effort to place the problem on an understandable scale. While historians do their best to remain neutral, I have no doubt, the history we are all taught is inevitably a selected narrative representing only a few perspectives at best. Once you begin to throw in complicating factors like changing social values and parties with vested interests in preserving certain legacies, history becomes far more complicated and dynamic than we might realize. Music history is no different.

The composers and performers and artists that students are taught in school comprise a selected historical narrative. And, because music is 100% subjective, neutrality doesn’t really exist. For as long as I have been alive, there has existed a canon that is meant to represent the definitive pinnacle of music. They are the all time great artists and their works and history is presented as the legacy of every musician alive today. As far as everybody else? Yeah, sorry too bad.

This is all changing — for the better

Artists, composers, producers, performers, writers, and historians are mounting challenges to this canon. Across genres and eras, there are people rightfully proclaiming that there is more to music than Bach and The Beatles and, further yet, there is more music than that which is produced in Europe and America.

Please, don’t get me wrong, people have been saying all of this for a very long time. However, it feels like a sea change is happening now and these challenges are sticking in a way that they haven’t before. All of it has resulted in what feels to me like a very exciting time in which we as a culture are reassessing our values and expanding our once narrow historical narrative into one that has room for many more voices. Not to mention a lot of great music.

One book in particular has brought me back to that place of being excited about music history — precisely because it dares to expand the canon.

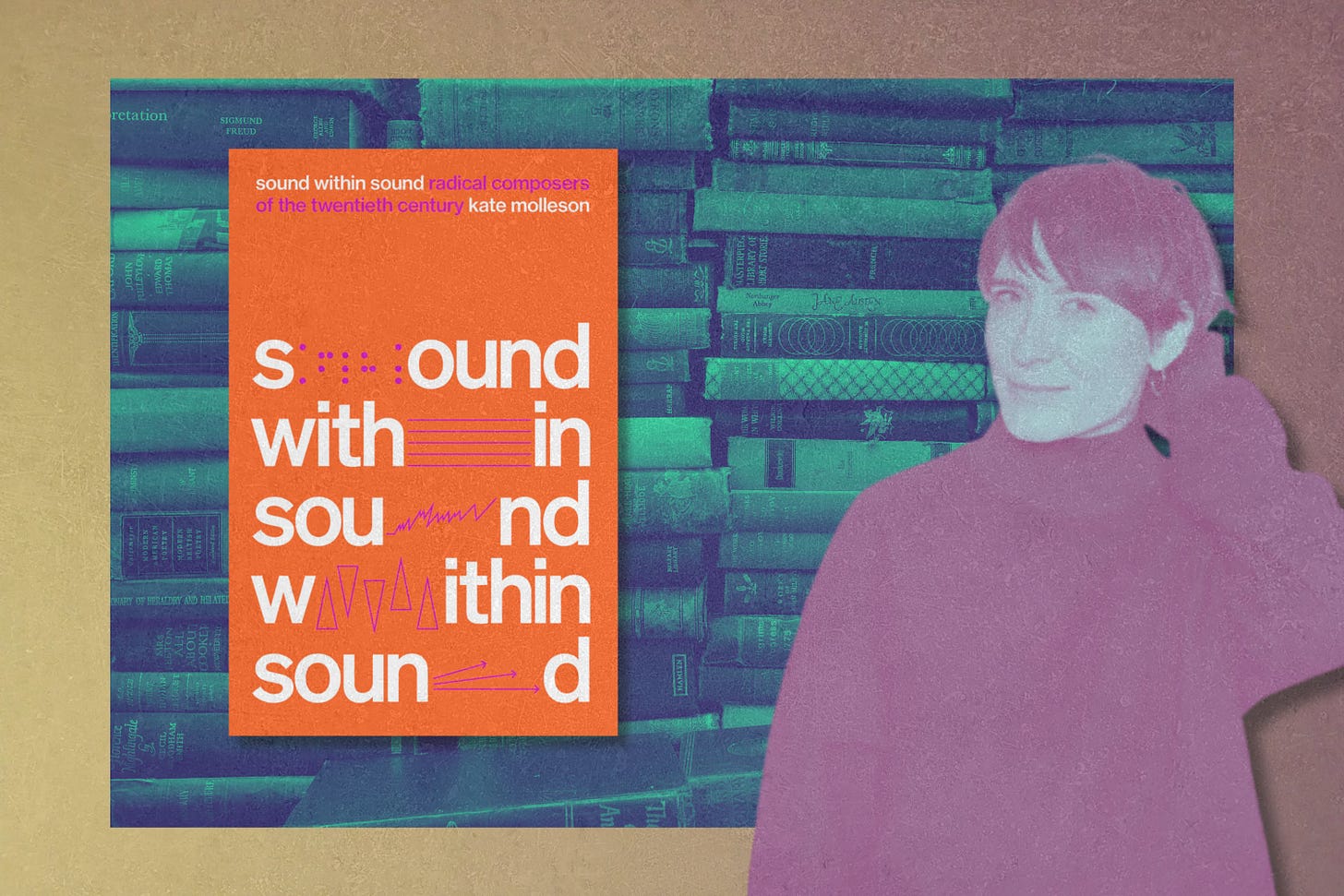

Sound Within Sound by Kate Molleson

We’re nearly 25 years removed from the 20th century. Some historians argue that 25 years is the point at which something definitively passes from the realm of current events into that of an historical event. Enough time has passed that we can look back, see what has happened, and feel settled on the matter.

That doesn’t seem to be the case as far as classical music is concerned. For a lot of fans, writers, and critics classical music seems to have lost the plot a bit during the 1900s. There are many people today who do not understand how music went from the lush romanticism of Brahms at the end of the 19th century to the “chaos” of atonality less than 50 years later. Alex Ross’s much-lauded The Rest is Noise did much to help clarify that question. While Ross’s book is excellent in framing these changes, it does so only within the contexts we already know and with a familiar cast of characters — mainly the well-known European and American composers of the 20th century.

This is where Sound Within Sound comes into the picture. Kate Molleson argues that the canon must be expanded and, until it is, we can never really understand the music of the 20th century, let alone how it’s connected to us today. Molleson then precedes to prove her point in the ten composer profiles that make up this book.

From Walter Smetak’s penchant for inventing strange new instruments, to Muhal Richard Abrams expanding the role improvisation can play in classical music, or the criminally overlooked and pioneering electronic work of Elaine Radigue, Sound Within Sound sheds light on a musical history of the 20th century for the rest of us. The artists presented within this book are the connective tissue linking the work that so many of us do today to the past.

The greatest triumph of this work is perhaps the diversity of the composers presented. Sound Within Sound tells a musical history of the 20th century from a global perspective, allowing more people than ever to see themselves reflected in the pages of a history book. Above all, Molleson’s work should be celebrated for this.

The only thing I would dare ask for is a sequel. Read this book.

Let’s listen to some of these incredible composers’ music

Julian Carrillo’s gorgeously hazy music that exists somewhere between love song and night sweat.

Ruth Crawford’s powerful and arresting string quartet from 1931.

Else Marie Pade was doing things in 1958 that I’m still not entirely sure how to do now. Otherworldly, synth-y textures abound.

Let Emahoy Tsegue-Maryam Guebrou’s magical piano playing uplift you.

Annea Lockwood’s Piano Burning is the most badass thing ever.

Why it is so important to constantly reassess our musical history

The past events that we choose to celebrate and venerate define the values we espouse today. And as far as music is concerned, I’ll happily go on record and say that those values aren’t worth shit if they leave people behind. If we want our art form to thrive, then we should welcome as many voices and ideas into the fold as we can. To welcome the ideas of diverse musical traditions today, we have to recognize the past contributions of those diverse musical traditions.

I know for a fact I am not the only musician who grew up frustrated that he had to learn about countless dead German dudes while simultaneously being told that the rock and jazz music I loved growing up wasn’t sophisticated enough to be studied in school. As I’ve grown older, I’ve come to wonder why my teachers spent so much time teaching the music of German composers (of which I have ancestry) as opposed to, say, Middle Eastern composers (of which I also have ancestry)? It has left me feeling connected to one part of my own heritage while feeling completely alienated from another. I can’t imagine how frustrating it must be for musicians who come from cultures entirely outside of the American musical mainstream. Why have they been left out? The answer at its best is thoughtlessness and at its worst is far more dubious.

The point is that we exist in a state of constant opportunity. At any moment, we can elevate, use, teach, and discuss so many interesting musical ideas that have long been left off of the table.

Until next time.

Quick Hits

Listen to my new single “Run.” It’s a song about frustration, realization, and release. Glitchy drums, a string quartet, and big vocals. Listen here.

I’m on YouTube now. Check out instrument design tutorials, production breakdowns, and music videos. Subscribe here.

I currently have capacity to take on two more music production students. I offer private one on one lessons over Zoom. You can sign up for lessons here.